Yummy bingsoo for the first day of summer 2013.

It makes me miss halo-halo.

@ Sweet Berry in Fairax, VA

Friday, June 21, 2013

Thursday, June 13, 2013

Only in America: The American Dream

By SARAH MERVOSH

Staff Writer

Published: 18 November 2012 11:12 PM

Updated: 19 November 2012 01:44 PM

Just after sunrise, the morning rush picks up at 7-Eleven. Igor Finkler — industrious immigrant, Beatles lover and the man who melted a CEO’s heart on national TV — rings up coffee for the bleary-eyed.

Wearing jeans and a red-and-black 7-Eleven shirt, he could be any immigrant making his way in America as a convenience store clerk. Except that behind him — past the cigarettes and near the taquito grill — is a framed photograph. There he is in a blazer and tie smiling with Oprah Winfrey and the head of 7-Eleven.

Finkler’s life changed in 2010 when he was featured on Undercover Boss, a CBS reality show in which corporate executives disguise themselves and work within their own companies. Finkler, then a truck driver for 7-Eleven, was paired with “Danny,” who was actually Joe DePinto, 7-Eleven’s president and CEO. After the show aired, DePinto stunned Finkler with a grand gift — his own store, on East Campbell Road near North Central Expressway in Richardson.

Two and a half years later, Finkler is learning the meaning of the American dream: Success doesn’t come without hard work — even when you’re handed the keys to your livelihood. He works more, sleeps less and gets paid about the same as when he drove trucks.

Still, having been thrust into leadership, Finkler is determined to make his store a haven of sorts for his customers. He gives an extra dollar in change now and again, paid out of his own wallet. He remembers names and asks about families. He smiles and does his best to make customers smile back.

With these small gestures, Finkler is doing his part to prove that anything — even a 7-Eleven — can be a force of good in this world.

‘Undercover Boss’

Finkler is the man behind the register. The guy who cleans the bathroom and mops up spills. The one who’d be easy to ignore.

But he’s also an immigrant from Kazakhstan who holds a master’s degree in electrical engineering from his home country. He’s a former Soviet soldier who now keeps small American flags on shelves in the store’s backroom. He came to the U.S. in the mid-’90s seeking a better life for his wife, daughter and son.

In 2009, Finkler had been working as an overnight delivery driver for 7-Eleven for 10 years. One day, his boss told Finkler to train a new employee — something he’d done many times before. But this time, he was asked to sign paperwork so cameras could film him for a documentary about entry-level training.

The next day, Finkler was summoned to company headquarters. There, he learned the cameras had been for Undercover Boss and his “trainee” had been DePinto. At first, Finkler worried he might be fired. But DePinto loved him.

“He blew me away,” the CEO said at the time. “His truck was immaculate. Every store we went to, the employees loved him, and when I asked about overtime, he said I should be able to get my work done in eight hours. Any more would hurt the company.”

After the Undercover Boss episode aired in 2010, Oprah invited Finkler onto her show. That’s when DePinto surprised him with keys to his own 7-Eleven. The gift meant Finkler didn’t have to pay franchise fees or make a down payment, costs that total about $239,000 for an average store.

“I didn’t expect that the boss will appreciate it so much,” Finkler says. “To me, I just did my job.”

The American dream

Running on energy drinks and water, Finkler has been at work since 4 a.m. It’s now after 7, and he raps his knuckles on the counter during a rare lull. He plays air guitar to the Creedence Clearwater Revival song coming from overhead speakers.

At 50, he is thin and balding. He wears a Bluetooth headset in one ear. Each time the front door opens, Finkler perks up. He throws his hands into the air and shouts, “Good morning! How are you, my friend?”

Finkler sets an example for his employees to follow. He engages his customers in a way that’s atypical for convenience stores — he once wore a sombrero and green sunglasses for a burrito sale.

He doesn’t allow himself to get tired, or, if he does, to show it. He remembers an expression from the Soviet army: “There are no sick soldiers — only dead or alive.” Finkler says he “simply cannot have a bad day.”

He puts in 60 to 80 hours a week. The store sees about 800 customers each weekday, and last month’s sales were up 8 percent from the previous year. But that’s still 30 percent below the market average. Finkler says that’s normal for the first few years of business, but not good enough. “Less than excellence is not accepted,” he says.

“He won’t quit until the job is done. He kind of expects others to act in the same way,” says his son, Sergei Finkler, who works at the store. “I often have to remind him, you know, this is not the army.”

Even when Finkler goes home for the night, he wonders how the store’s doing. “He’ll tell me, ‘I woke up and I couldn’t sleep. I was thinking about the business,’” Sergei, 23, says. “If it was his choice, he’d put a sleeping bag here in the office and just stay here.”

For all the hours Finkler puts in, he hasn’t given himself a raise since becoming a franchisee. He says he makes about $600 a week after taxes — slightly more than he made as a truck driver, but much less if you figure it by the hour. He gives any extra money the store makes to his employees, whom he considers family.

Finkler doesn’t mind hard work. But in time, he hopes he’ll be able to work a little less and sleep a little more. Then he might have more time for hobbies like having movie nights with his wife, reading Mark Twain novels and skydiving with his family.

Until then, Finkler sits in the back room, surrounded by Airheads, packaged cookies and Matador beef jerky. He bobs his head as he sings the refrain from the Beatles’ “Across the Universe” — and almost gets it right.

“Nothing’s gonna change my mind …”

‘Their paradise place’

Finkler knows money can’t buy him love — the Beatles taught him that. He doesn’t work for the pay. He works for these people: Jason, who has a newborn baby. Melissa, who looks forward to joking with Finkler in the mornings. Sam, who feels like he’s cheating if he goes to a different 7-Eleven.

“I love my customers,” Finkler says. “My customers are my guests, for whom I was waiting all my life.”

And they love him back. They know Finkler by name. They rave that the store is clean and the employees are friendly. They say they’ve never been to another convenience store like it.

“He makes your morning,” says Melissa Cohn, who stops in daily. “He really makes me want to come in.”

On his desk at home, Finkler keeps a ceramic tile that quotes Gandhi: “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

He wants his 7-Eleven to be a therapeutic environment — a place where customers can relax, laugh and forget about their problems. “This is their paradise place,” he says.

As Finkler works the register, Hope Cunningham Brown comes in. She works nearby at AT&T and often buys lottery tickets from him.

On this day, she tries her luck on a different number than usual. She starts to walk away, only to circle back when she realizes she forgot to pay for her coffee. Finkler waves her away and pays for it himself.

Walking away with coffee in hand, she smiles.

But Finkler beams.

Forgiveness

"Forgiveness is a heavy-duty word. I don’t know that I forgave my father. I’m not even sure what that means................Those conversations don’t cancel out the years of trauma and neglect. But neither does the bad cancel out those final moments of grace. Both are true. I hold both in my heart, and I am grateful. In the year before he died, I got to love my father — some."

MODERN LOVE

Do Not Adjust Your Screen or Sound

By HEATHER SELLERS

Published: June 13, 2013

My computer screen filled with bosom. The bosom belonged to Dawn, the activities director at the care center in Florida where my father was living. She leaned over her laptop and shouted, “Can you hear us?”

Brian Rea

I leapt out of my chair, closed my office door. I was shaking. When Dawn stepped aside, I would see the father I hadn’t seen in years.

And never sober. My father smoked and drank around the clock. And he didn’t just chase women — he lunged for them. He met any intervention with violent rage. The large sum of money he inherited from his father slipped away to homeless drifters and lady friends from bars. He missed my graduations, my wedding, every birthday, every need. I was in my late 30s when I realized: This relationship might be too hard.

So I let him go. From afar, I orchestrated assisted living, necessary paperwork and medical power of attorney.

I didn’t see him. Until now.

I watched Dawn’s face, her long brown hair.

“We can hear you, but we can’t see you,” she said.

In the background, I heard an old man saying, “Wah, wah, wah,” as if asking for water. How happy my father would be, I thought, if he were the one seeing the cleavage up close on the screen. There’d been that, too: porn addiction. And cross-dressing. So much chaos and confusion in this man. Recently, I’d decided he had most likely suffered from mental illness. But I’d never found a way to know him or understand his rage.

Now, here he was, Fred Sellers, at 80. I hadn’t seen him in so many years. His bright eyes roved around the screen, intensely curious. He still had his thick white hair and gigantic eyebrows. His stroke-frozen claw hand was clutched over his heart. He worked his good hand to the keyboard. I was afraid he was going to break our connection.

“Daddy,” I said. I sounded so small. My throat hurt. I did not want to cry. I was at work, wearing mascara and a white blouse; I had to teach class in less than an hour. “You look so good.”

“Well, hell,” he said, peering hard at the screen. “Where you been, girl child?”

His stroke-affected speech was heavy on vowels, light on consonants. But every word was as clear to me as always. He looked better than ever. Was this the first time I’d seen him sober?

“Can you see me, Daddy?”

“No!” he shouted, banging his good hand on the keyboard.

I examined the green button on my screen, just under his chin: “Video.” It was on. Then I remembered: Since his stroke, when he said “no” he meant “yes,” and “yes” meant “no.” He did see me. “Isn’t this great?” I said, pressing tissues to my face.

“No!” he shouted. “No, no.”

I smiled.

Over the years, friends, clergy members and relatives urged me to visit my father, while others urged me to never see him again. When I visited, I always regretted it. When I didn’t, I regretted that, too.

But children of negligent parents have complicated needs. Now that my father was in a nursing home and couldn’t drink, hurt anyone or destroy himself, I felt overwhelmed in a good way by the love that rushed in. Now that my father fit into a desktop-size box — my computer screen — the proportions seemed manageable.

My father and I started talking, thanks to Dawn, every Friday afternoon. Online video calls gave me my father, gave him to me in a safe, manageable format. Here, in a box, was a man I could love.

“Dawn says you’re doing pretty good,” I said.

“No!” he said, his whole body nodding yes. “No!”

“It is so good to see you,” I said.

“Oh, gosh,” he said. “Oh gosh, honey. Look at you.” This last would sound to the untrained ear as “Oh, osh. Unnie. Ooo. Ah. Ooo.”

He beamed. I’d never seen my father really happy before. I’d never seen his love for me shine through. But here it was.

At this safe distance, I couldn’t get enough of him. We spent a lot of time just staring at each other. He peered hard into the screen, trying to capture every bit of information, looking happily overwhelmed, and fiercely confused. One day, I was pleased he was wearing a green striped shirt I’d mailed, and I told him how nice he looked.

He looked down at himself and back up at me, shaking his head, as if to say, “Life’s a mystery.” He looked bemused, bereft and philosophical all at once. And always well shaven, well fed. We’d been estranged forever, yet now we were having the best relationship we’d ever had.

After that first conversation, when the adrenaline kept us both going for an hour, he tired quickly, and our talks were brief. He got bored; his attention wandered. I sensed he was looking around Dawn’s activity room for cookies, hidden treats.

One day I showed him photographs of his babyhood, his parents and his own young family, me as a baby. He looked intently, saying the names of each person. When I told him my book was coming out and showed him a mock-up of the cover, he said: “No kidding. Amazing, amazing.”

He looked so proud. Stunned, but proud. Often he asked me, in his garbled way, how my house was, and my teaching. Finally he was asking me questions about my life, noticing I had one. My Dad was with me, there was just less of him. Which turned out to be a good thing.

That fall, at one of my department meetings, a colleague from the office next to mine said, “Your video calls are disturbing others.”

“I know it’s loud,” I said. “My father can’t hear me unless I shout. I apologize. But it’s the only time of day I can talk to him. The calls are brief. Please be patient.”

I wanted to say: “This is all we have, this fragile shouting. It’s 10 minutes or so a week. And it won’t last much longer.”

I tried to find another weekday time that could work for all of us. I tried to find another place to set up my computer. But I didn’t try very hard. Some part of me, I admit, wanted to disturb my colleagues. Some part of me wanted to yell my father into the world: “Don’t you see? I have a father! My Dad loves me. And I love him.”

“I love you,” I shouted at the end of each conversation.

“Ooo ooo ooo ooo,” he said, every time, as he zipped out of the screen (“I love you, too”).

After Christmas that year, my father went to the activities room less and less. Then in February he didn’t go at all. A couple of times Dawn took her personal laptop into his room, and I’d see him in his bed, and he’d wave his good hand, look at me for a bit, smile wanly, then drift back to sleep.

Finally Dawn broke the news to me: lung cancer. I flew to Orlando and spent three days with him. We held hands and laughed a lot. I showed him old photos. I read him a book I’d salvaged from my childhood.

That evening, after dinner, he pointed to his chest.

“Does it hurt?” I asked.

He nodded. “Is it bad?” he asked me.

“It’s not good,” I said.

“Dammit.”

I held his hand while he slept. The laptop phone calls had given me a new template for my father. I couldn’t have just come down and seen him otherwise. We’d made a new relationship online, me and the smaller Fred.

The cancer was a slow-growing kind. They said six months, maybe three years.

Two weeks later, he was dead. Pneumonia. As he passed, a nurse — an angel — in I.C.U. held the phone to his ear. She said, “When he hears your voice, he smiles.”

In the end, we had just barely a year. But I got what I wanted: to be a normal daughter. And after he died, I got to have some profoundly normal grief. The last words he heard me say were “I love you,” and his last to me, said in his way, were “I love you, too.”

Forgiveness is a heavy-duty word. I don’t know that I forgave my father. I’m not even sure what that means. What happened between us at the end of his life feels more simple and complex than forgiveness.

Those conversations don’t cancel out the years of trauma and neglect. But neither does the bad cancel out those final moments of grace. Both are true. I hold both in my heart, and I am grateful. In the year before he died, I got to love my father — some.

Heather Sellers, the author of “You Don’t Look Like Anyone I Know,” is at work on a new memoir about her family.

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

10 ways we sabotage our own success

10 ways we sabotage our own success

BY CHINIE H. DIAZ

POSTED ON 06/02/2013 9:23 PM | UPDATED 06/02/2013 9:55 PM

POSTED ON 06/02/2013 9:23 PM | UPDATED 06/02/2013 9:55 PM

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

|

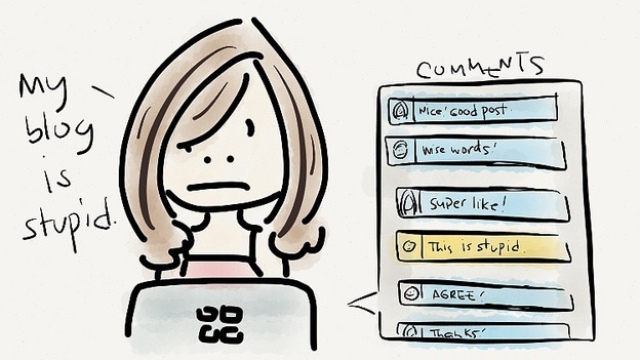

In my last post, I talked about how toxic friendships can ruin our lives and happiness, but to be honest, we don’t always need other people to do that. We can achieve misery and ruin pretty well on our own. Sad to say, we are often our own worst frenemy. And if we aren’t careful, we can do much more damage to ourselves than friends, family, or any other external influences ever could.

We all have an inner critic. Sometimes this is a good thing that keeps our less attractive qualities in check. Other times, however, this inner critic can take on Supervillain proportions and seriously cripple our ability to achieve happiness and success.

Dr David Burns, author of Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, says that the key to avoiding this type of self-sabotage is to turn the critic into a coach instead.

Before we can do this, however, we first need to identify which of our inner criticisms are helpful, and which are actually the result of a warped way of thinking.

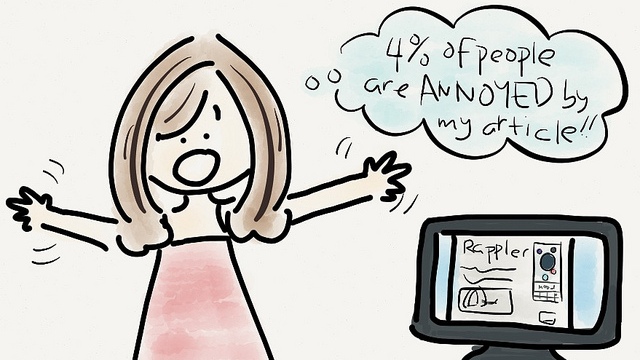

According to Dr Burns, there are 10 patterns of distorted thinking that warp our outlook on life — and if you can identify and catch these types of thoughts as they occur, you have a better likelihood of being able to turn them around.

1. All-or-nothing thinking

Everything is black or white, good or evil, victory or defeat. If something isn’t perfect, then it’s no good. If you aren’t perfect, you’re a failure.

2. Over-generalization

You look at single, isolated negative events and see them as a never-ending pattern of failure and defeat.

3. Disqualifying the positive

When something good happens, you ignore it, pass it off as a fluke or something that doesn’t count, or turn it into something negative (e.g., something to feel guilty or unworthy about).

4. Mental filtering

When presented with both positive and negative things, you filter out all the positive and focus only on the negative.

5. Jumping to conclusions

Like some sort of doomsday fortune teller, you automatically assume negative reactions or outcomes, even when there’s no evidence to support your conclusion.

6. Magnification and minimization

You make mountains out of molehills by exaggerating the importance of negative experiences, failures or shortcomings. Or, you magnify the positive traits of others, exaggeratedly downplaying your own.

7. Emotional reasoning

You think your negative emotions and feelings reflect reality, assuming that just because you feel something, then it must be true. You then base your decisions on these negative emotions instead of on actual facts.

8. Should statements

You insist on a set of “rules” that you and everyone else should follow based on your own version of reality. When you don’t adhere to these rules, you feel guilty, and when others don’t adhere to them, you feel hurt or resentful.

9. Labeling and mislabeling

You describe people (especially yourself) using absolute, negative labels (loser, racist, troll, cheater, etc).

10. Personalization

You see yourself as the cause of negative events and outcomes which, in fact, you were not primarily responsible for.

I’m not sure if these struck any chords for you, but I saw quite a few that I could relate to. And the funny thing is, even as I identified with them, I was thinking, “That’s so stupid.” This is precisely why we need to identify these types of cognitive distortions — so we can call them out for what they are, and adjust them accordingly.

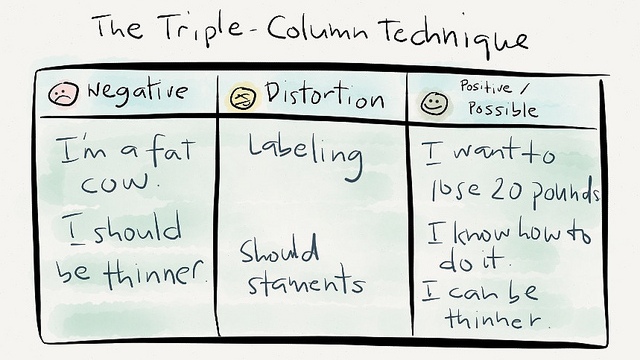

In his book, Dr Burns recommends using a Triple-Column Technique to turn your inner critic into acompadre, and it’s pretty easy and surprisingly effective. Here’s how it works:

- Train yourself to write down your negative thoughts as they come to you.

- Divide a piece of paper into 3 columns.

- In the 1st column, write down the negative thought (self-criticism).

- In the 2nd column, identify the distorted thinking behind it.

- In the 3rd column, write down your rational response (self-defense).

Tip: Psychologist Tamar E. Chansky, PhD, suggests using the “Power of Possible Thinking” instead of trying to turn self trash-talk into chirpy, positive statements that will just set off your internal lie detector.

"We feel a lot of pressure to turn it all around and make it positive," Chansky says. "But research has found that when you're down and out and force yourself to say positive things to yourself, you end up feeling worse." – Huffington Post

If you can turn your negative thoughts into something possible and actionable, you’re much more likely to feel encouraged and be motivated to change. And that matters, because our thoughts are so much more powerful than we can imagine. If we want to change our lives, we really do need to change our thoughts first. – Rappler.com

When depression kicks in

When I moved to the United States, I was full of promise and plans. I wanted to be a lot of things. I wanted to conquer the world. But to my reality, this isn't easy as a walk in the park. The American Dream is not a walk in the park. I had to literally work my way to have that dream.

Recently, I have been battling with an inner demon questioning me, agonizing and torturing me of who I want to be.

I have always been the person who wants to help and will help. But I am starting to think that I actually need help.

I am 24 but I feel like I am in my forties. I support my Father, my Brother and recently my boyfriend. CJ lost his job last month. I am trying to make my salary work for three people here in the United States. Yes, he just got a job and will start next week but his salary is not even close to mine. With that, I have to keep my 2nd job just so we can have extra money to pay our Credit Card debt and extra money for other issues such as car or medical concerns.

Money is a big thing for me especially because I don't have anyone to lean to here. I always believe it has been me.

I came here with $13 dollars and now I have an apartment and my own car all because I worked my but off. At one point I had 3 or sometimes 4 jobs because I wasn't responsible of myself but I had other people relying on me.

If other people had medals for their achievements, I had milestones. I wouldn't forget the feeling of a having a new used car, moving into an apartment, getting promoted at work. The feeling of accomplishing these makes me feel that I have a purpose in this world.

But is it not always joy. There are days that I am just tired and lost. I have to push myself to wake up and finish the day because I need the money to live by the day. I always remind myself that I have to work because no one else will help me. I cannot afford to reach hard bottom.

This thinking also makes me anti social of some sorts. In all my three years in the US, most people who befriended me befriended me because they needed something. They needed a ride, a job, to sell me something, cosign on an apartment, join an activist group. In my life, those are the times that I felt most used.

The Hi and Hellos and How are yous just becomes superficial to me because I know after those statement there is something that will be asked from me. Also, I never really felt the concern. It seems like those statements are just for the sake of conversation. They always felt dry. But when I do ask that to a person, I mean it. It just seems unfair that the intent is never always mutual and fair.

So what is fair? I do believe in Karma. I believe that when you do good things, the good things go back to you. But up to what point do I have to give myself?

I remember when I was helping a family. I was bothered everyday because they needed something. I gave them a hand but they want the arm better yet they want my whole body. I want to help but how do you a help a person/family who just wants to suck the life out of you.

I never thought I would be as lonely as I am in the United States. At least in the Philippines, I had somewhere to run, I had someone to seek refuge to -Mama. In here, I just have myself. I might have my boyfriend but he would never understand me fully.

I believe I coped up with all my problems by just dealing with it and getting over it. I just go by the day. I enjoy when my life is so fast because I don't remember that I actually have problems to deal with. But I dread the times, when the world seems slow and quiet because that is when the little demon of depression kicks in and reminds me of how alone and miserable I am.

I don't know how to combat it. All I know is that he is telling the truth. I have succumb to a world that just takes away the life in. That I have settled to this so called land of dreams. That I have accepted comfort zones instead of new horizons. That I feared success because I am scared to actually fail.

I have faced that I should find the flaws rather than see the light. I have become this robot rather than the free person that I should have been. I am now a person that I don't know.

I have changed.

I pray. I try. I try to talk to him and maybe he will understand. But I how I do I relay what bothers me when I myself is not sure. Maybe it is me. Maybe I was born with. Maybe. Maybe.

I hope I can find the answers soon because really I don't know where to get from here.

I miss myself. The person who really belongs to this body. The soul that enriches my being. The girl that wants to change the world and conquer her dreams. I miss the passion that keeps me going. I miss the love. I miss the belief that the world is still good.

So today, I still in front of my computer trying to do something to make the day go by with my part time job. I pray that somehow the times goes faster so I can home and sleep and escape the real world. The real world is awesome but for now I seek refuge in a dream called sleep.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)